The following is an article that appeared in the Baltimore Sun,

written by Frederick N. Rasmussen of the Sun staff:

During the 1960s, Baltimoreans anywhere near a radio

at 6 a.m. were summoned from their slumbers by the deep ringing

of a gong followed by a chorus "like the one that accompanied Richard

Burton as he walked the last mile in "The Robe," according to the

Sunday Sun Magazine.

With the stage set, an organ flared up, sounding for all the

world as if it were providing the musical background for Bela

Lugosi's grand entrance down a staircase in "Dracula," or any

other RKO horror movie of the 1930s.

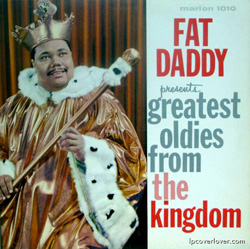

And then came the voice of Paul "Fat Daddy" Johnson, the "300-pound

King of Soul," with its rhythmic incantations and machine-gun-like

soul jive. His voice and delivery have been described as "precise

and sonorous" yet "high-pitched and pressurized." His outrageous

monologues rolled forth with a "gospel-like fervor."

"Hear me now," he'd hiss into the mike. "Up from the very soul

of breathing. Up from the orange crates. From the ghetto through

the suburban areas comes your leader of rhythm and blues, the

expected one - Fat Daddy, the soul boss with the hot sauce. Built

for comfort, not for speed. Everyone loves a fat man! The Fat

Daddy show is guaranteed to satisfy momma. I'm gonna go way out

on a limb on this one, Baltimore. Fat poppa, show stoppa."

Ringing bells gave way to several pulses of the organ followed

by the recorded voice of a young girl saying, "Lay

it on me, Fat Daddy, lay it on me."

"Fat Daddy, your king, and I've got soul for you. This is for

all the foxes wakin' up this morning. Here's a soul kiss for ya,

mmmmmmmmh! From the lips of the high priest, from the depth of

a fat man's soul..."

Born in 1938, Baltimore native Paul Johnson was raised near

Pennsylvania Avenue, graduated from Douglass High School, where

he was sports editor of the school paper, and later received a

bachelor's degree in journalism and communications from the University

of Maryland, College Park.

While in college, he began working as a disc jockey at the new

Albert Ballroom in the 1200 block of Pennsylvania Ave. and the

Royal Theater and was influenced by the flamboyant style of another

local deejay, Kelson "Chop Chop" Fisher.

After working briefly at a Danville, Va., radio station, Fat

Daddy returned to Baltimore, subsequently working for radio stations

WSID, WITH, and finally WINN.

Standing like a general before a battle, Fat Daddy stood before

a studio console where his show took to the airwaves, somehow

arising out of an organized chaos of records, commercials and

his endless patter. Here's how the Sun Magazine described the

scene in a story in 1966:

"Fat Daddy bobbing rhythmically in a constant wash

of sound from the speaker on the wall is manipulating this equipment

with a great deal of flair, snapping cartridges into the tapecasters,

slapping 45's on the turntables, delivering finger-jabbing commercials,

fiddling with a row of dials, answering the telephone, calling

up for the weather report, stringing it all together with this

supersonic, rhyming delivery and all the while maintaining a running

conversation with whomever happens to be in the room."

Fat Daddy and his music were popular with African-Americans but

also found a wide audience among whites.

"I programmed my show for the Negro originally," he said in

the magazine article. "Rhythm and blues used to be race music.

But Fat Daddy has become such a large character with everybody

that now I program for white and black both. Music brings people

closer together."

In 1971, Fat Daddy left Baltimore to do national promotions

for record companies, working for Motown, Atlantic, and Capitol

Records. He was 40 when he died in Los Angeles in 1978. Esquire,

Cashbox, and Billboard have acclaimed him as one of the top five

R&B disc jockeys in America, while Record World magazine called

him simply the No. 1 soul man in the nation.